By Joanna Grey Talbot

Charlotte Hawkins Brown

Sometimes those who make the greatest impact are the ones who work passionately and quietly behind the scenes, not seeking fame or fortune. They seek the limelight only when absolutely necessary to champion the cause they believe in, not to bring themselves recognition. Charlotte Hawkins Brown was one such person. She overcame many obstacles to put action to her belief that through a quality education and the social graces African-American children could rise above their circumstances.

Brown was born June 11, 1883, in Henderson, North Carolina. She was born Lottie Hawkins but in high school decided to change it to Charlotte Eugenia Hawkins because she thought it sounded more elegant. Yet, as many African-Americans in post-Reconstruction North Carolina did, Charlotte, her mother, Carrie, and nineteen members of her extended family moved to Boston, Massachusetts, in 1888 to pursue a better life and greater opportunities away from Jim Crow laws.

In Cambridge, Carrie met and married Nelson Willis, a native North Carolinian, in 1889. Willis worked as a janitor and day laborer, while Carrie was a laundress and boarded African-American Harvard students and other African-Americans from North Carolina. During these years in Cambridge Brown was raised to be independent and self-sufficient and to take full advantage of her education.

Before graduating from high school, she had a chance encounter with a woman who would play a large role in her future career. One afternoon while sitting on a bench and rocking the carriage of the child she was babysitting, this woman walked by and saw her reading works by Virgil. She stopped to ask where she went to school and then went on her way. Brown found out the next day from her principal that the woman was Alice Freeman Palmer, the president of Wellesley College. Palmer had called to find out who Brown was. They did not come in contact again until Brown graduated from high school in 1900 and decided to attend a two-year college and work towards becoming a teacher.

Alice Freeman Palmer

Knowing her family’s financial situation, Brown wrote to Palmer for advice. Before Palmer responded she contacted Brown’s high school mentor who vouched for her character and drive. Palmer then offered to pay for part of her tuition and any “incidental expenses at any normal school in Massachusetts.” From there began a strong relationship that would last for the next two years until Palmer’s sudden death in 1902. In the fall of 1900 Brown matriculated at the state normal school in Salem, Massachusetts. She quickly advanced in her studies and had every intention to graduate but the next year she received an offer she could not refuse. Another chance encounter changed the course of her life.

One day in the spring of 1901 she was headed to school on the train. A woman moved to sit down next to her and introduced herself as the field secretary for the American Missionary Association, which operated schools for African-Americans throughout the South. The woman told her they were looking for qualified African-American teachers. Brown was very interested and the woman agreed to send her information. She was offered either a job in Florida or in North Carolina; she chose her home state.

In October 1901, Brown arrived in Sedalia, North Carolina, and took over the teaching at Bethany Institute. It was a one-room school, which met in a church; she lived in the loft upstairs. Yet, the following spring, as a result of dwindling funds, the AMA decided to close all of its one-room and two-room schoolhouses. Brown decided to stay anyway, wanting to give the children of Sedalia the same opportunities she was given as a child. The summer of 1902 she headed back to Massachusetts to raise funds to keep the school open. Through meeting with businessmen and walking to all the resorts in Gloucester to tell the wealthy about the school, by the end of the summer she had raised all the money she needed. The minister, Reverend Baldwin, of the church where the school was held donated fifteen acres and the blacksmith shop, which she converted into the first classroom building. Although starting with very little, from there Brown went on to create Palmer Memorial Institute, in honor of her mentor and benefactor, Alice Freeman Palmer.

Alice Freeman Palmer Building

By 1905 she and her assistant, Lelia Ireland, raised enough money to lay the foundation of Memorial Hall. In the next twelve years the Institute grew to four buildings. In the beginning, Brown’s philosophy was very similar to that of Booker T. Washington, wanting her students to not only focus on academic training but also vocational training. She wanted them to go out into the world with not only knowledge but skills for a job as well. Yet, in the post-Depression years she made the decision to change the school’s focus to that of a secondary and junior college school, which was focused more on the liberal arts, instead of vocational and agricultural studies.

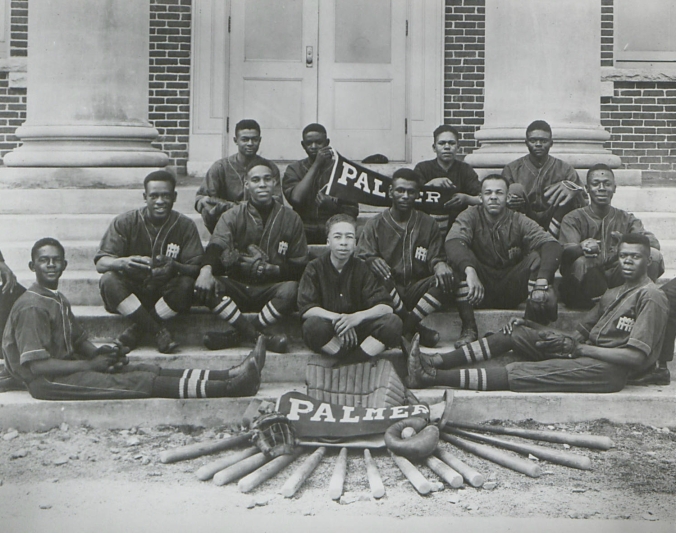

1920 Palmer Memorial Institute Baseball Team

Brown traveled extensively to continue to raise funds for the school. In 1927 she gave 67 speeches. Yet, as much as she cared about the school and its students, she also cared equally for the community of Sedalia. She didn’t isolate the school from the local citizens, inviting them to all the school’s events and creating a Parent-Teacher Association for the parents. One of the many things she did to help the community was creating the Sedalia Home Ownership Association as a way to help educate the citizens on how they could own their homes. By the 1930s 95% of the families in the community did so.

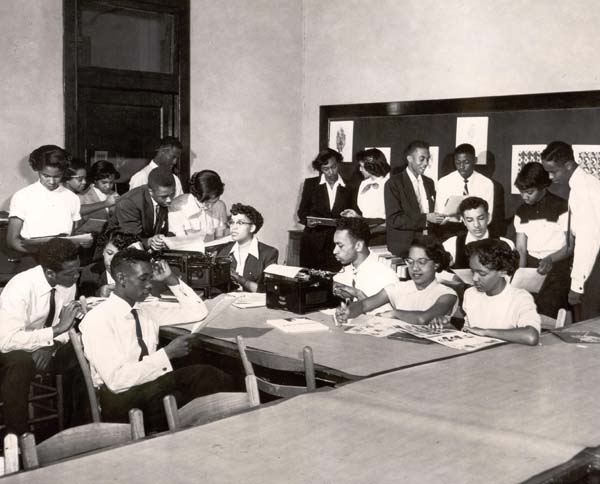

The school continued to grow and began to attract students from outside North Carolina. By 1934 the school consisted of 400 acres and 14 buildings, all of which were steam-heated and lit by electricity. In 1937, when the first public school in Sedalia opened, most of the high school students switched to attend there, so Brown once again changed the Institute’s focus to that of a prep school and finishing school.

Students at Palmer Memorial Institute

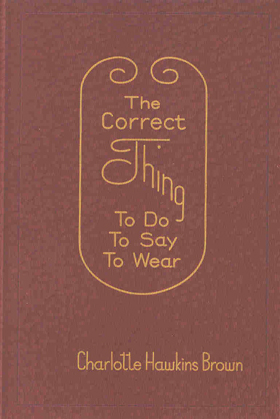

Through her fundraising trips, Brown continued to bring attention to the merits of Palmer Memorial Institute and by the 1940s it had become the premier finishing school for African-American students in the country. Since its inception manners and correct behavior had been a pillar of the Institute’s mission, leading Brown to write and publish in 1941 The Correct Thing to Do – to Say – to Wear. In the introduction Brown stated her purpose for writing it was “to help one to know and practice the art of kindness, the art of graciousness, the art of expressing one’s best self when alone, thus developing the habit of doing the correct thing without effort or apparent notice.” She strongly believed that good manners made young people more self-confident and secure and without proper manners a good education would not be of much use. Brown said that,

“in order for the Negro to get even half the recognition which he may deserve, he must be even more gracious, more cultured […] if he would gain a decent place in the sun. […] Using the social graces as one means of turning the wheels of progress with greater velocity on the upward road to equal opportunity and justice for all.”

The book would go on to have five printings, with the last revision in 1965.

By the 1950s her health was in decline and she retired in 1952, naming Welhelmina Crosson as her successor. Brown remained as a financial advisor and continued to live on the campus in her house, Canary Cottage. Then on January 11, 1961, she died of heart failure at a hospital in Greensboro and was buried on the school grounds.

The school tried to continue without its biggest supporter and with de-segregation causing a drop in enrollment. Unfortunately, it was closed at the end of the 1970-1971 school year and in November of 1971 Bennett College took over the grounds. For the most part the buildings remained empty, so in 1987 the state bought the buildings and grounds and opened it as a historic site – the first in the state that honored a woman and an African-American. Her papers are housed at the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University.

Charlotte Hawkins Brown for 68 years had made an impact not only on her students and their families, but the country as a whole. She worked tirelessly to show that through education and the social graces that all people could live side by side in peace. Devoting her life to this cause, she left a legacy of hope, equality, and the idea that all it took to accomplish something was hard work and determination.

Charlotte Hawkins Brown Museum: http://www.nchistoricsites.org/chb/

Images courtesy of the State Library of North Carolina, Charlotte Hawkins Brown Museum, and Radcliffe Institute for Advance Study at Harvard University.

An amazing story – and an amazing woman!

LikeLike